Thursday, December 9, 2021

Since Virginia's new red-flag law was signed by the Gov. Ralph Northam last year, according to data from the Virginia State Police, law enforcement officials across Virginia have issued 170 emergency substantial risk orders to temporarily confiscate firearms from people courts have determined could be dangerous. That includes 32 in Fairfax County, six in Arlington and five in Alexandria. Police officers and sheriffs deputies have also used the law in so-called "Second Amendment sanctuaries," including 13 risk orders in Virginia Beach and seven in Hanover County.

"These risk orders have been used across the commonwealth, in urban cities and rural counties," said Lori Haas, Virginia state director for the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence. "If a person is at risk of harm to self or others, it would be prudent for family members and loved ones and law enforcement to temporarily separate him or her from his firearm so that until the crisis passes, the person is not at risk of injury or death to him or herself or others."

Since Republicans swept all three stateside officers and seized control of the House of Delegates last month, gun enthusiasts have been plotting to unravel many of the gun-violence prevention measures Democrats instituted over the last two years. One of their top priorities is getting rid of the red-flag law, which narrowly passed the state Senate in 2020 with a vote of 20 to 20. Democratic Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax voted to break the tie to send the bill to the governor. Now that a Republican will be in that seat, the only way to stop the law from being overturned may be for Senate Democrats to prevent it from getting to the floor.

"Red flag laws leave the person in crisis alone," said Philip Van Cleve, president of the Virginia Citizens Defense League. "They can still kill themselves. They do nothing except take his guns away."

According to the Virginia Department of Health, Virginia had 1,036 gun deaths in 2018. About two-thirds were suicides, and one-third were homicides.

WHEN DEMOCRATS seized control of the General Assembly last year, one of their top priorities was implementing new gun-violence prevention measures. Although they failed to adopt an assault weapons ban, they were able to require background checks and ban guns from local parks and government buildings. One of the signature gun bills was the red flag law, which allows citizens to alert authorities when a friend or family member may be in danger of posing a danger to themselves or others. That sets the stage for a judge to conduct a hearing where law-enforcement officials or prosecutors make the case that firearms should be temporarily confiscated.

"I'm pleased to see that it's being used, and I'm pleased to see it's being used all around the state," said Del. Rip Sullivan (D-48), who introduced the House version of the bill. "As it becomes more well known both to the public and to law enforcement, I wouldn't be surprised if it gets used more."

One of the sticking points with the process is that the individual in question is not present in the initial court hearing. The judge makes the ruling to confiscate the guns in an "ex parte" hearing where the accused has no opportunity to present a defense. After the judge orders the emergency risk order, law enforcement officials serve the document and confiscate any known firearms for 14 days. Then the court holds a second hearing where the accused gets to mount a defense. At that point the judge can extend the order for 180 days or return the weapons. Gun-rights groups say the process is a violation of individual liberties, although supporters of gun-violence prevention say similar measures are taken when people have concerns over mental health or custody of children.

"There are other places in the code that type of process is done as a first step, and then you address it later," said Sen. George Barker (D-39), who introduced the Senate version of the bill. "They get an opportunity to contest it in court. So they do have a right to deal with it fairly quickly."

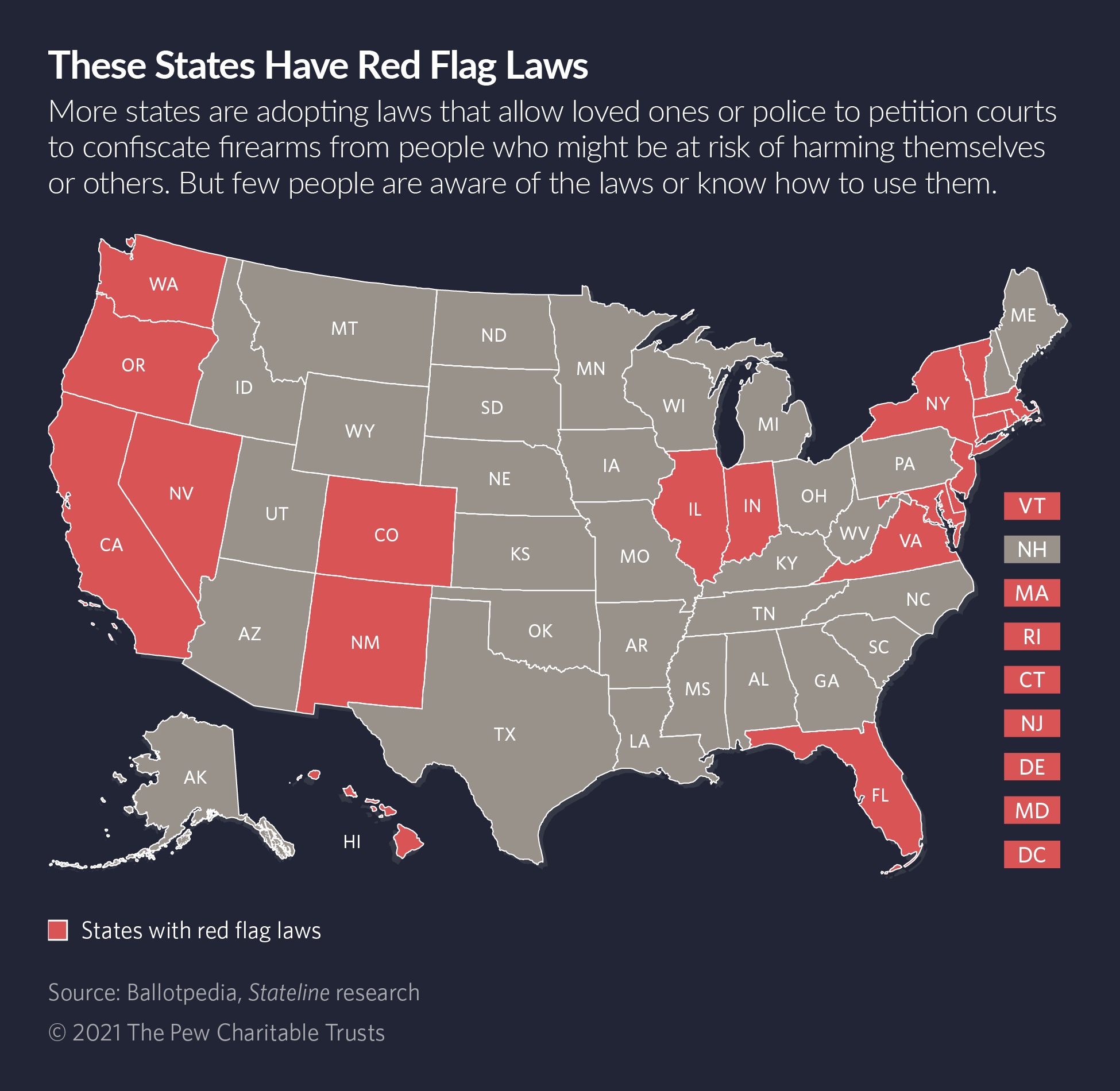

NINETEEN STATES and the District of Columbia have enacted some form of emergency risk orders, which are also known as gun-violence restraining orders and extreme risk-protection orders. Connecticut was the first state to enact a red flag law back in 1999 following a mass shooting at the Connecticut Lottery headquarters in 1998 when a disgruntled accountant killed four of his supervisors and then shot himself. The shooter has previously attempted suicide and was being treated for depression.

"Potential changes to the law could streamline the gun-removal process and make it easier for police to take preventive action when appropriate," wrote Duke University professor Jeffrey Swanson in a study of the Connecticut law. "One such change, which was suggested by an expert respondent interviewed for this study, would be to allow police to remove guns immediately with probable cause."

The tension between risk to safety and jeopardy of civil liberties was a sticking point for lawmakers in Virginia when they were debating the bill last year. Republicans argued that violating liberties in the name of protecting safety was a slippery slope, and that the same logic might be used to strip other rights. Many Republicans openly doubted that the legislation would accomplish anything.

“What purpose does it serve to serve an order on him telling him to turn over his firearms?" asked Sen. Richard Stuart (R-28). "Couldn’t he create havoc with a myriad of other things, and if this person is mentally disturbed shouldn’t we deal with that first?”

When the bill was debated in the state Senate, Republicans tried unsuccessfully to amend the bill restricting it to people who might do harm to themselves, not others.

“The research has shown that people who intend to kill themselves with a firearm are hindered when the firearm is removed and suicide is much less likely to occur," said Sen, Creigh Deeds (D-25). "In the states where this legislation has passed that’s what the studies show.”

NOW THAT THE law has been in effect for more than a year, the contours of its effectiveness are coming into view. Some activists who pushed for the law say the numbers from the Virginia State Police show the law isn't being used enough. Considering the scope of the problem, they say, law-enforcement officers should be receiving more tips from citizens who are concerned that someone they know might be on the verge of committing the next mass shooting.

"Of the million people in Fairfax County, 32 is not a lot," said Paul Friedman, founder and executive director of the advocacy group Safer Country. "If the average citizen is paying attention to their neighbors and identifying people who are under enormous stress and have guns, we can prevent a lot more potential problems."

That's why Friedman is currently working with Fairfax County Supervisor Rodney Lusk on a public awareness campaign to let people know about the new law and the role they can play in stopping future gun violence. The Board of Supervisors approved the campaign last summer, and since that time a working group has adopted the slogan "prevent a gun tragedy, speak up." Friedman is hoping that Lusk will work with the other supervisors to include funding for the campaign in the next budget, potentially hiring a staffer to oversee the campaign and extend its reach.

"Right now, awareness is low." said Lusk in a written statement after the board approved the initiative last summer. "I hope this effort helps the new law better achieve its intended goal of having guns in responsible hands."